From its inception to the present day, Tantra has challenged religious, cultural and political norms around the world. A philosophy that emerged in India around the sixth century, Tantra has been linked to successive waves of revolutionary thought, from its early transformation of Hinduism and Buddhism, to the Indian fight for independence and the rise of 1960s counterculture.

The Sanskrit word ‘Tantra’ derives from the verbal root tan, meaning ‘to weave’, or ‘compose’, and refers to a type of instructional text, often written as a dialogue between a god and a goddess. The exhibition features some of the earliest surviving Tantras (see image below). These outline a variety of rituals for invoking one of the many all-powerful Tantric deities, including through visualisations and yoga. Requiring guidance from a teacher, or guru, they were said to grant worldly and supernatural powers, from long life to flight, alongside spiritual transformation.

Many texts contained rituals that transgressed existing social and religious boundaries – for example, sexual rites and engagement with the taboo, such as intoxicants and human remains. Tantra challenged distinctions between opposites by teaching that everything is sacred, including the traditionally profane and impure.

The rise of Tantra

The development of Tantra in medieval India coincided with the rise of many new kingdoms across the subcontinent after the breakdown of two major dynasties, the Guptas in the north and the Vakatakas in the southwest. Although this led to political precariousness, there was also a great flourishing of the arts. Many rulers were drawn to Tantra’s promise of power and public temples often incorporated Tantric deities as guardians.

This included the Tantric Hindu god Bhairava, seen above. He famously decapitated the orthodox creator god Brahma to show the superiority of the Tantric path and used his skull as a begging bowl. Early Tantric practitioners (Tantrikas) emulated his fearsome and anarchic appearance in order to ‘become’ him, while rulers worshipped him in order to strengthen their political positions.

One of his early followers was the poet-saint Karaikkal Ammaiyar, who abandoned her role as an obedient wife to become his follower. Tantric initiation was open to people from different social backgrounds. This challenge to the caste system made Tantra especially appealing to women and the socially marginalised.

Divine feminine power

The Tantric worldview sees all material reality as animated by Shakti – unlimited, divine feminine power. This inspired the dramatic rise of goddess worship in medieval India. Tantric goddesses challenged traditional models of womanhood as passive and docile in their intertwining of violent and erotic power. Their characteristics were tied to a uniquely Tantric tension between the destructive and the maternal.

The seductive but dangerous Yoginis were shapeshifting goddesses who could metamorphose into women, birds, tigers or jackals as the mood took them. Initiated Tantrikas sought to access their powers, from flight and immortality to control over others. The Yogini above is part of a group that would have once been enshrined in a Yogini temple. Her earrings are made of a dismembered hand and a cobra, and she has fangs.

The Yoginis were believed to offer protection to kingdoms against epidemics or enemy forces and assist in the acquisition of new territories. Most Yogini temples were circular and unique in their roofless design – you can see an example below. The exhibition will feature an immersive and imaginative recreation of this space.

Tantric yoga

The allure of Tantra, with its promise of longevity and invulnerability, retained a hold over those in positions of power between the 16th and 19th centuries, including Rajput, Mughal and Sultanate rulers. One form of Tantric practice that became especially popular was Hatha yoga (‘yoga of force’).

Yogis used complex postures and muscular contractions to direct the flow of breath. Techniques included visualising the goddess Kundalini, an individual’s source of Shakti, as a serpent at the base of the spine. Around her is a network of energy centres known as chakras, each of which contains a deity. Together, they make up the ‘yogic body’. Through breath control, Kundalini rises like a current, infusing the chakras with power. Awakening Kundalini became the practitioner’s ultimate goal. This is what is being visualised in the painting below, a loan from the British Library. This is very much about transformation in the world, via the body, rather than transcendence of it.

The spread of Tantra across Asia

Also known as Vajrayana, the ‘Path of the Thunderbolt’, Tantric Buddhism flourished in Eastern India. Buddhist monasteries studied and taught the Tantras, and attracted pilgrims from across Asia. This led to the rapid transmission of Vajrayana teachings. Tibet saw the founding of major monasteries which became the new political players and often rivalled one another.

Instrumental in the transmission of Tantric teachings from India to the Himalayas were the Mahasiddhas or Great Accomplished Ones. Their life stories are filled with miraculous events and they became especially popular in Tibet. Many engaged in sexual rites and carried out practices involving impure substances in cremation ground settings. Their goal was to confront limiting emotions such as attachment, fear and disgust. Most are shown as semi-naked and shaggy-haired yogis. Some carry skull-cups and wear human bone ornaments to imitate Tantric deities. Six are shown here, including Saraha in the centre. He holds an arrow, symbolic of single-minded concentration and a reference to his guru, who was a female arrow-smith.

One of the themes the exhibition explores is the role of divine union. Tantric Buddhist texts and images use gender to articulate the two qualities to be cultivated on the path towards enlightenment, wisdom and compassion. These are visualised as a goddess (representing wisdom) and a god (representing compassion) in sexual union, as we see with this Tibetan bronze. In Tibet this is known as yab-yum or father-mother. The goal is to internalise these qualities by visualising the deities uniting within the body through meditation.

Tantra and revolution in colonial India

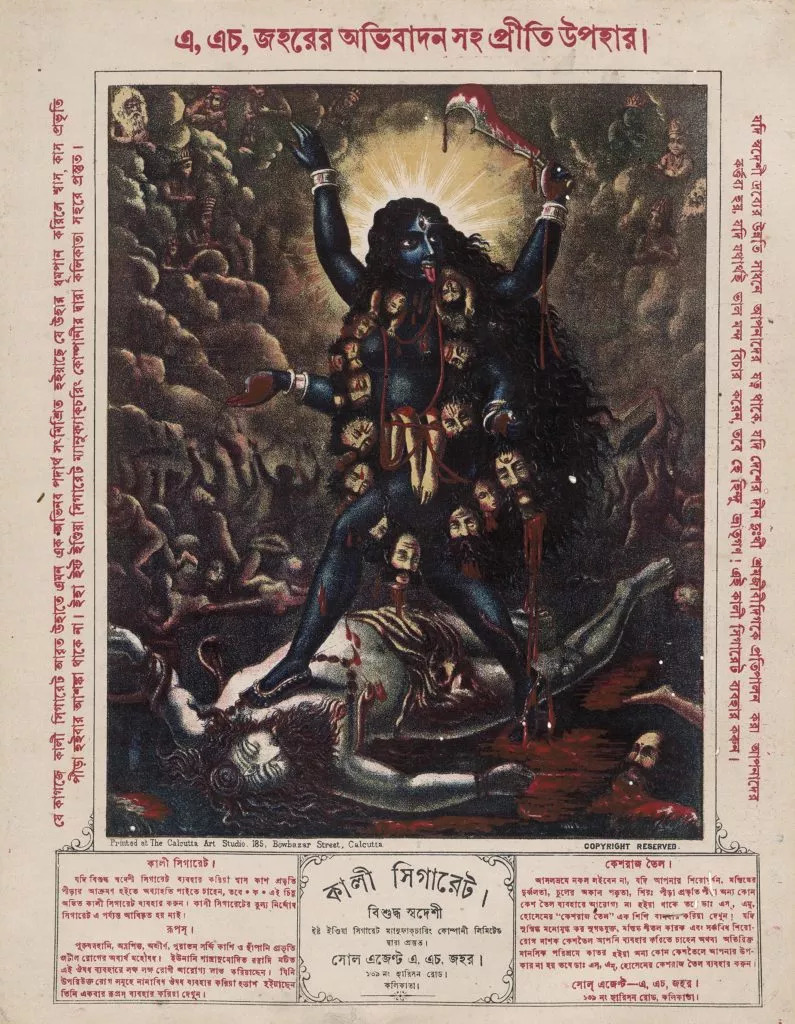

The Tantric goddess Kali was widely worshipped in Bengal. She was heralded as a ruthless yet compassionate Mother by the Bengali mystic and poet, Ramprasad Sen. His verse resonated at a time of crisis in Bengal, intensified by the rise of the British East India Company. Devotion to Kali as an icon of strength increased, promoted through poetry and public festivals.

Kali was regarded by many British officials as a threat to the colonial enterprise, and Bengali revolutionaries effectively exploited these fears by reimagining her as a symbol of resistance and a manifestation of India personified. This is evident in prints produced by printmakers such as the Calcutta Art Studio, established in 1878. The example below continued to circulate after 1905, when Bengal was partitioned by the British to weaken the growing independence movement. A colonial administrator identified the decapitated heads in this print as suspiciously British-looking, leading to its censorship.

The art of Tantra

Both before and after Indian independence from British rule in 1947 and the emergence of India and Pakistan as independent nation states, South Asian artists forged modern national styles rooted in the pre-colonial art of the past. Many were inspired by Tantra’s engagement with social inclusivity and spiritual freedom. In the 1970s, artists associated with the Neo-Tantra movement adopted certain Tantric symbols and adapted them to speak to the visual language of global modernism, particularly Abstract Expressionism.

The painting above by Bangladeshi artist Biren De reflects the influence of the concentric shapes of mandalas, which frame luminous central deities. This centre point is also understood as an expression of cosmic creation.

Tantra in the UK and the US

In the UK and the US in the 1960s and 1970s, Tantra had an impact on the period’s radical politics, where it was interpreted as a movement that could inspire anti-capitalist, ecological and free love ideals. Tantra was reimagined as a ‘cult of ecstasy’ that could challenge stifled attitudes to sexuality. Here a pair of London-based designers draw on Tantric images of deities in union to communicate this idea.

Another poster advertises the Human Be-In festival, held in San Francisco, which heralded the summer of love in 1967. Yoga and meditation were promoted as transformative practices that could inspire minds to challenge the status quo. The poster includes a portrait of a yogi taken in Nepal. Yogis captured the popular imagination in the West as countercultural role models.

Tantra today

Today, 200 years of shifting interpretations have left many misconceptions about what Tantra is, or what it actually involves. Tantra is not independent of Hinduism and Buddhism but has pervaded and transformed both traditions from its inception. As a worldview, philosophy and set of practices, Tantra is as alive as ever. Sects in India, including the Aghoris, reveal the enduring power of the movement. Their practices include smearing their bodies with the ash of burnt corpses from funerary pyres, as seen here, an act which is traditionally deemed polluting.

For the Aghoris, transgressive practices are an expression of the Tantric assertion that all is sacred and there is no distinction between what is conventionally perceived as pure and impure, just as there is no distinction between the self and the divine. By shattering society’s cultural conditioning of the mind, the Aghoris transcend ego-led emotions such as fear and aversion and instead nurture a non-discriminating attitude that draws on the repressed power of the taboo.

Tantra and the female gaze

In the contemporary art world, female artists have harnessed Tantric goddesses through the bodies of real women, evoking them in a feminist guise. The title of this almost three-metre tall mixed-media painting, Housewives with Steak-knives, challenges the stereotype of the submissive wife confined to the kitchen. It is by the Bengal-born British artist Sutapa Biswas. Here the ‘Housewife’ as Kali wears a garland of heads that the artist describes as figureheads of authoritarian patriarchy.

With this exhibition, we are offering the chance to gain a deeper understanding of Tantra so you can explore the diversity and vitality of its philosophies and practices, and the richness of its artistic traditions. Above all, we hope you’ll be stimulated and challenged to question your own ideas about the nature of the divine.

This article was first published by The British Museum